The Detroit Rock ‘n’ Roll scene in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s was unlike anything else happening in the world at the time. New York was certainly tough, but there was an artistic flair that added a touch of respectability to it. The West Coast scene certainly had its moments, although the hippy-dippy flower-power movement took away some of its thunder. But Detroit? It was a hotbed of unbridled energy, attitude, and bravado. While Motown was in many ways the soul of Detroit, the Rock ‘n’ Roll rumble in the streets was loud and often frightening. But it was also invigorating and electrifying. It was raw and pure. It was Garage Rock with the power of Punk and Metal (neither of which were musical genres at the time!) yet it could also be artsy like the East Coast, and hippy-dippy like San Francisco and L.A. It was a melting pot of attitudes and ideas. And it was where the Grande Ballroom was born.

Unlike any venue before or since, the Grande was not just a concert hall – it was a meeting place for creative minds, disenchanted youth and people of all race, class, and creed. It may have promoted shows by local and touring bands, yet it also embraced the sexual revolution, psychedelia, the drug culture, and, most importantly, freedom of expression. The club Detroit bands like MC5, The Stooges, The Frost, The Third Power and SRC were regulars, while The Who, Pink Floyd, B.B. King, Led Zeppelin and many other major bands would always play there while on tour. The Grande became THE venue to play for every major Rock band once they had already conquered the East and/or West Coast. For some, it was even more important! The Grande was the brainchild of Russ Gibb, who some remember as one of the instigators of the ‘Paul Is Dead’ hoax of the late ‘60s (or was it a hoax?). Along with controversial counter-culture figure John Sinclair, they turned an old 1920s dancehall into something truly mind-blowing. Although the Grande shut its doors more than four decades ago, it remains one of Rock’s most iconic venues.

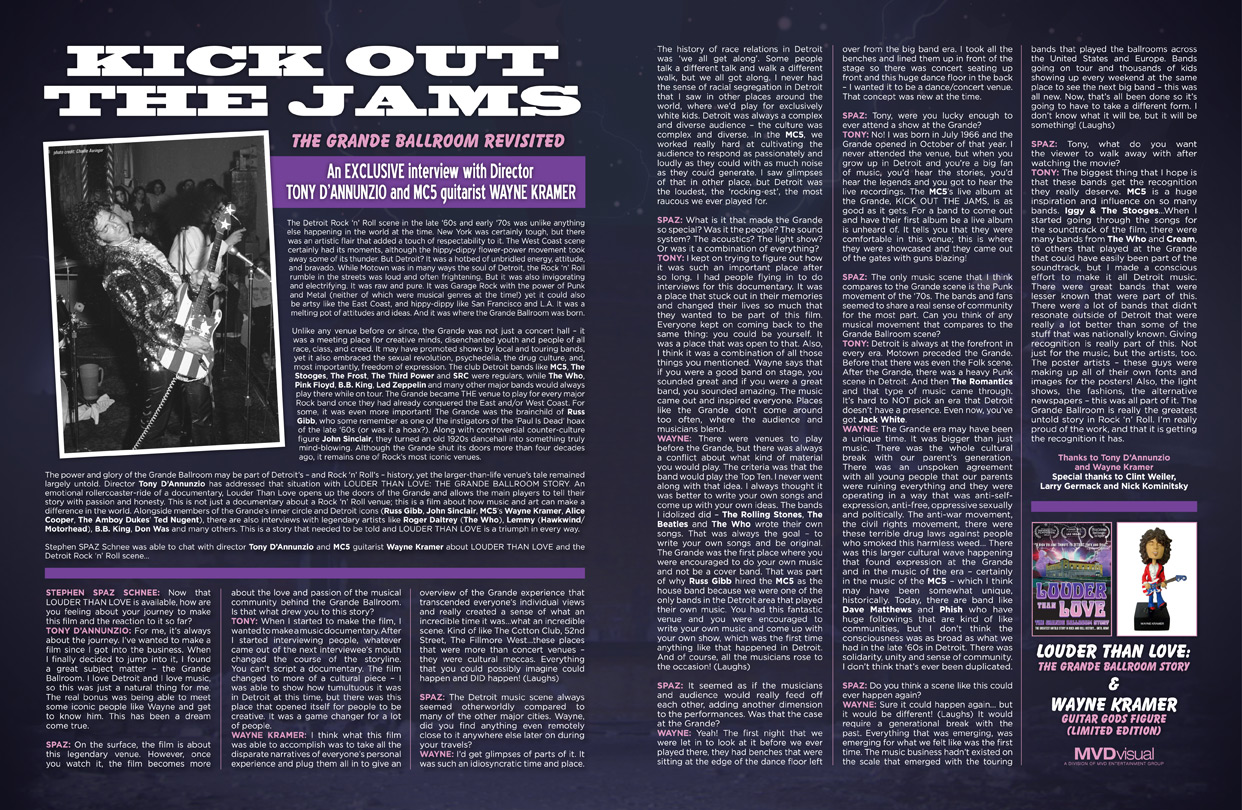

The power and glory of the Grande Ballroom may be part of Detroit’s – and Rock ‘n’ Roll’s – history, yet the larger-than-life venue’s tale remained largely untold. Director Tony D’Annunzio has addressed that situation with Louder Than Love: The Grande Ballroom Story. An emotional rollercoaster-ride of a documentary, Louder Than Love opens up the doors of the Grande and allows the main players to tell their story with passion and honesty. This is not just a documentary about a Rock ‘n’ Roll venue; this is a film about how music and art can make a difference in the world. Alongside members of the Grande’s inner circle and Detroit icons (Russ Gibb, John Sinclair, MC5’s Wayne Kramer, Alice Cooper, The Amboy Dukes’ Ted Nugent), there are also interviews with legendary artists like Roger Daltrey (The Who), Lemmy (Hawkwind/Motorhead), B.B. King, Don Was and many others. This is a story that needed to be told and Louder Than Love is a triumph in every way.

Stephen SPAZ Schnee was able to chat with director Tony D’Annunzio and MC5 guitarist Wayne Kramer about Louder Than Love and the Detroit Rock ‘n’ Roll scene…

STEPHEN SPAZ SCHNEE: Now that Louder Than Love is available, how are you feeling about your journey to make this film and the reaction to it so far?

TONY D’ANNUNZIO: For me, it’s always about the journey. I’ve wanted to make a film since I got into the business. When I finally decided to jump into it, I found a great subject matter – the Grande Ballroom. I love Detroit and I love music, so this was just a natural thing for me. The real bonus was being able to meet some iconic people like Wayne and get to know him. This has been a dream come true.

SPAZ: On the surface, the film is about this legendary venue. However, once you watch it, the film becomes more about the love and passion of the musical community behind the Grande Ballroom. Is that what drew you to this story?

TONY: When I started to make the film, I wanted to make a music documentary. After I started interviewing people, whatever came out of the next interviewee’s mouth changed the course of the storyline. You can’t script a documentary. The film changed to more of a cultural piece – I was able to show how tumultuous it was in Detroit at this time, but there was this place that opened itself for people to be creative. It was a game changer for a lot of people.

WAYNE KRAMER: I think what this film was able to accomplish was to take all the disparate narratives of everyone’s personal experience and plug them all in to give an overview of the Grande experience that transcended everyone’s individual views and really created a sense of what an incredible time it was…what an incredible scene. Kind of like The Cotton Club, 52nd Street, The Fillmore West…these places that were more than concert venues – they were cultural meccas. Everything that you could possibly imagine could happen and DID happen! (Laughs)

SPAZ: The Detroit music scene always seemed otherworldly compared to many of the other major cities. Wayne, did you find anything even remotely close to it anywhere else later on during your travels?

WAYNE: I’d get glimpses of parts of it. It was such an idiosyncratic time and place. The history of race relations in Detroit was ‘we all get along’. Some people talk a different talk and walk a different walk, but we all got along. I never had the sense of racial segregation in Detroit that I saw in other places around the world, where we’d play for exclusively white kids. Detroit was always a complex and diverse audience – the culture was complex and diverse. In the MC5, we worked really hard at cultivating the audience to respond as passionately and loudly as they could with as much noise as they could generate. I saw glimpses of that in other place, but Detroit was the loudest, the ‘rocking-est’, the most raucous we ever played for.

SPAZ: What is it that made the Grande so special? Was it the people? The sound system? The acoustics? The light show? Or was it a combination of everything?

TONY: I kept on trying to figure out how it was such an important place after so long. I had people flying in to do interviews for this documentary. It was a place that stuck out in their memories and changed their lives so much that they wanted to be part of this film. Everyone kept on coming back to the same thing: you could be yourself. It was a place that was open to that. Also, I think it was a combination of all those things you mentioned. Wayne says that if you were a good band on stage, you sounded great and if you were a great band, you sounded amazing. The music came out and inspired everyone. Places like the Grande don’t come around too often, where the audience and musicians blend.

WAYNE: There were venues to play before the Grande, but there was always a conflict about what kind of material you would play. The criteria was that the band would play the Top Ten. I never went along with that idea. I always thought it was better to write your own songs and come up with your own ideas. The bands I idolized did – The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and The Who wrote their own songs. That was always the goal – to write your own songs and be original. The Grande was the first place where you were encouraged to do your own music and not be a cover band. That was part of why Russ Gibb hired the MC5 as the house band because we were one of the only bands in the Detroit area that played their own music. You had this fantastic venue and you were encouraged to write your own music and come up with your own show, which was the first time anything like that happened in Detroit. And of course, all the musicians rose to the occasion! (Laughs)

SPAZ: It seemed as if the musicians and audience would really feed off each other, adding another dimension to the performances. Was that the case at the Grande?

WAYNE: Yeah! The first night that we were let in to look at it before we ever played there, they had benches that were sitting at the edge of the dance floor left over from the big band era. I took all the benches and lined them up in front of the stage so there was concert seating up front and this huge dance floor in the back – I wanted it to be a dance/concert venue. That concept was new at the time.

SPAZ: Tony, were you lucky enough to ever attend a show at the Grande?

TONY: No! I was born in July 1966 and the Grande opened in October of that year. I never attended the venue, but when you grow up in Detroit and you’re a big fan of music, you’d hear the stories, you’d hear the legends and you got to hear the live recordings. The MC5’s live album at the Grande, Kick Out The Jams, is as good as it gets. For a band to come out and have their first album be a live album is unheard of. It tells you that they were comfortable in this venue; this is where they were showcased and they came out of the gates with guns blazing!

SPAZ: The only music scene that I think compares to the Grande scene is the Punk movement of the ‘70s. The bands and fans seemed to share a real sense of community for the most part. Can you think of any musical movement that compares to the Grande Ballroom scene?

TONY: Detroit is always at the forefront in every era. Motown preceded the Grande. Before that there was even the Folk scene. After the Grande, there was a heavy Punk scene in Detroit. And then The Romantics and that type of music came through. It’s hard to NOT pick an era that Detroit doesn’t have a presence. Even now, you’ve got Jack White.

WAYNE: The Grande era may have been a unique time. It was bigger than just music. There was the whole cultural break with our parent’s generation. There was an unspoken agreement with all young people that our parents were ruining everything and they were operating in a way that was anti-self-expression, anti-free, oppressive sexually and politically. The anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, there were these terrible drug laws against people who smoked this harmless weed… There was this larger cultural wave happening that found expression at the Grande and in the music of the era – certainly in the music of the MC5 – which I think may have been somewhat unique, historically. Today, there are band like Dave Matthews and Phish who have huge followings that are kind of like communities, but I don’t think the consciousness was as broad as what we had in the late ‘60s in Detroit. There was solidarity, unity and sense of community. I don’t think that’s ever been duplicated.

SPAZ: Do you think a scene like this could ever happen again?

WAYNE: Sure it could happen again… but it would be different! (Laughs) It would require a generational break with the past. Everything that was emerging, was emerging for what we felt like was the first time. The music business hadn’t existed on the scale that emerged with the touring bands that played the ballrooms across the United States and Europe. Bands going on tour and thousands of kids showing up every weekend at the same place to see the next big band – this was all new. Now, that’s all been done so it’s going to have to take a different form. I don’t know what it will be, but it will be something! (Laughs)

SPAZ: Tony, what do you want the viewer to walk away with after watching the movie?

TONY: The biggest thing that I hope is that these bands get the recognition they really deserve. MC5 is a huge inspiration and influence on so many bands. Iggy & The Stooges…When I started going through the songs for the soundtrack of the film, there were many bands from The Who and Cream, to others that played at the Grande that could have easily been part of the soundtrack, but I made a conscious effort to make it all Detroit music. There were great bands that were lesser known that were part of this. There were a lot of bands that didn’t resonate outside of Detroit that were really a lot better than some of the stuff that was nationally known. Giving recognition is really part of this. Not just for the music, but the artists, too. The poster artists – these guys were making up all of their own fonts and images for the posters! Also, the light shows, the fashions, the alternative newspapers – this was all part of it. The Grande Ballroom is really the greatest untold story in Rock ‘n’ Roll. I’m really proud of the work, and that it is getting the recognition it has.

Thanks to Tony D’Annunzio and Wayne Kramer

Special thanks to Clint Weiler, Larry Germack and Nick Kominitsky